The donut shop in Carrboro on a busy morning with local map on the side wall.

We were in a hurry and the line in the upscale donut shop was long. This gave me a chance to take in the décor, in particular an enlargement of an old map of Chapel Hill and Carrboro.

This popular shop opened just over one year ago on the main commercial drag of

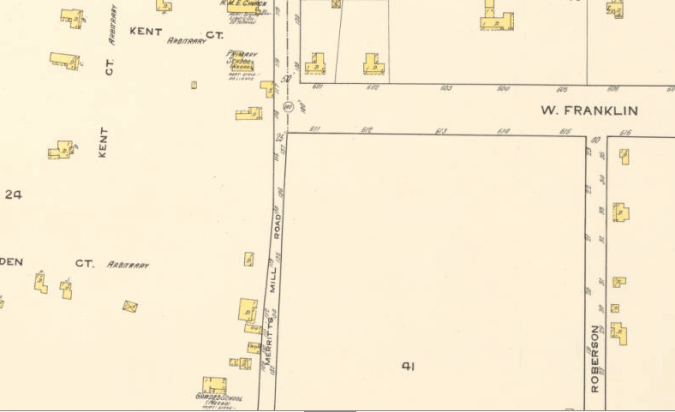

Carrboro, right next to the railroad tracks where Franklin turns to Main. The map shows this neighborhood, dated “1915.” Featuring prominently on the map are the various mills owned by Julian Carr, after which the town had been named just a few years prior to the year the map was drawn. Scattered among the mill buildings were a few houses, stores, churches, and a few schools, including the “Negro Primary School” and the “Negro Graded School.”

Carrboro, right next to the railroad tracks where Franklin turns to Main. The map shows this neighborhood, dated “1915.” Featuring prominently on the map are the various mills owned by Julian Carr, after which the town had been named just a few years prior to the year the map was drawn. Scattered among the mill buildings were a few houses, stores, churches, and a few schools, including the “Negro Primary School” and the “Negro Graded School.”

Detail of 1915 map of Carrboro and Chapel Hill showing the border area between the towns. Merritt Mill Road was an African-American enclave, as was Kent Ct. and Eden Ct. (also known as Tin Top for the metal roofing material). The Negro Primary school is located at the top of the page and the Negro Graded School, later known as Lincoln High, is located at the very bottom of the map.

These labels are a clear indicator of the town’s Jim Crow past.

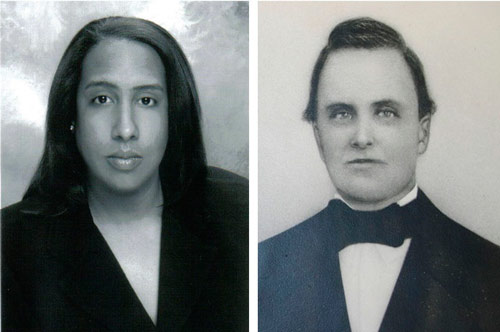

And yet, on the donut shop wall, the map is just a historic relic, a retro prop, a colorful reference to the place’s roots. But on closer look, the labels remind of an era in which the Klan was alive and well, Carrboro was a no-go zone for blacks, and white supremacy was the law. This was the time when the Silent Sam memorial, now the source of bitter controversy, was erected, and Julian Carr, the keynote speaker at its dedication in 1913 declared:

One hundred yards from where we stand, less than ninety days perhaps after my return from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.

from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.

At this time memorials and monuments honoring soldiers of the Confederacy were popping up all over the South, Klan activity was peaking, and Woodrow Wilson, an avowed racist and, in Carr’s words, “a distinguished son of the South,” was in the White House, all serving as very visible reminders that the racial order would be preserved even in the post-slavery South.

According to Jane Dailey, associate professor of history at the University of Chicago, “Most of the people who were involved in erecting the monuments were not necessarily erecting a monument to the past, but were rather, erecting them toward a white supremacist future.” (NPR, Aug 20, 2017)

Undoubtedly, Silent Sam and Julian Carr made the neighborhoods around the donut shop, which sits between the part of Chapel Hill known as Tin Top, where poor Blacks lived, and white working class Carrboro, scary places for Blacks. The tension created by dedication ceremonies celebrating the heroic deeds of Confederate soldiers must have been terrifying for many of the residents.

So, what makes it possible for such a map to function as colorful décor, an unproblematic, uncontroversial representation of a bygone era, a “commemorative landscape”? Few people, most likely including the shop owners, probably noticed the “Negro primary school” marker. But shouldn’t they have? Isn’t it obvious that any map of any Southern town would contain hints and markers of segregation? Don’t railroad tracks often signify a social divide? And aren’t right side and wrong side usually indicative of the color line? Do locals think that racial divides and violence associated with the Jim Crow South did not apply to a university town like Chapel Hill? And if so, isn’t this the problem with local lore– that white residents believe Chapel Hill wasn’t like the rest of the South, even as it was the “Southern” part of heaven?

I think that anyone who hangs a map like this on a wall must think about what the map tells us about the time it was created. This map is full of meaning, a visual reminder of an unjust social and political order. Such a sign of the past should raise questions and yet, as decor, it does the opposite. It normalizes and romanticizes by encouraging a comforting nostalgia. And while donuts should always be considered comfort food, the chapter of the town’s history on the wall should always make people stop and think about what that history meant for those who lived through it, as uncomfortable as that will be for some. The past is also our present.

I think that anyone who hangs a map like this on a wall must think about what the map tells us about the time it was created. This map is full of meaning, a visual reminder of an unjust social and political order. Such a sign of the past should raise questions and yet, as decor, it does the opposite. It normalizes and romanticizes by encouraging a comforting nostalgia. And while donuts should always be considered comfort food, the chapter of the town’s history on the wall should always make people stop and think about what that history meant for those who lived through it, as uncomfortable as that will be for some. The past is also our present.

After all, as the map says, it’s 1915, and “You are here.”