Slavery stole the identity of most African-Americans in this country. … It’s a wonderful experience to know who our distant ancestors are and to be able to tie it to a physical location.

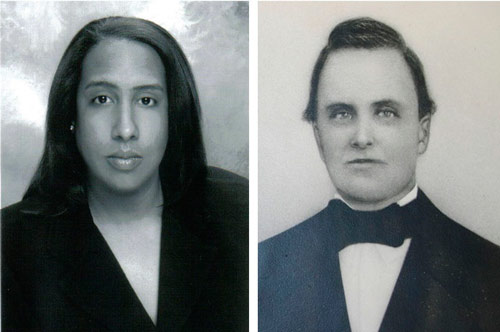

Deardre Green-Campbell

Until a few weeks ago, if you happened to be driving down Purefoy Road just off of Rogers Road in north Chapel Hill and you looked very closely, you might have caught a glimpse through the tangled vines of an old dilapidated house. Though you would have seen no plaques or signs, some of the long-time locals would have been able to tell you the story of the place, the Hogan-Rogers House, built in 1843 by Thomas Hogan, a farmer and a slaveholder. Though local preservationists have called Hogan a “middle class” farmer, the fact that he owned more than forty slaves at the time he built the house made him one of the largest landowners in the area. Excavations of the house suggest that many of them must have lived in the basement with its dirt floors.

The house was purchased from the Hogans by Rogers at the turn of the century. Rogers, an African-American farmer, lived there until the Depression forced him to give it up about a century after it was built in the 1930s.

If you were to stop and do a bit of trespassing, here is what you’d see:

When the house was demolished, the floorboards and basement were left intact. It’s possible to stand on the remains of the main floor view, peer down the old staircase, and look into what was once the basement, with very low ceilings and dirt floors.

Around back, you’d have a view of the brick exterior that shows a small basement window; look through the window, and you’d see what once was a working hearth where slaves would have cooked.

More important than the story of the house is the story of the people who lived in it and the people who can trace their histories to the people who lived in it more than 150 years ago. And thanks to Deardre Green-Campbell, we now know a lot more than we did a few years ago.

Deardre Green-Campbell (left), likely a direct descendant of Harriet Hogan, a slave, and slave-owner, William Hogan (right; pictured here in the mid-to-late 1800s), a son of Thomas Lloyd Hogan, the builder and original owner of the house. (Source: ibiblio)

Deardre wanted to confirm what she somehow suspected: that she is a Hogan, too, a descendant of a Hogan family member and a slave named Harriet. She was able to get a DNA sample from a Hogan descendant living in Brooklyn, and we now know that her hunch was correct. For Deardre that was a really important discovery because it gave her a place she now calls “home.”

But what does her discovery mean for the rest of us? That question should be answered on a personal level– and that’s why it’s so important to preserve the remaining traces of this house. If it remains a living testimony to the past– one that focuses on the integral part slavery played in the local economy and among the people who lived here.

In Louisiana, just north of New Orleans, some people had a similar vision when they turned an old plantation site into a museum which, unlike the state’s many other preserved plantations, focuses on the lives and legacies of the slaves who lived there (whitneyplantation.com). Its pedagogic value is clear to those who visit.

Here is what Mitch Landrieu, the mayor of New Orleans, had to say:

Go on in. You have to go inside. When you walk in that space you can’t deny what happened to these people. You can feel it, touch it, smell it.

And more importantly, here is what some of the young visitors have said:

After reading books upon books about plantation life, [the founders of the museum] decided that what was missing on River Road was the God’s-honest-truth about slavery.

I learned a lot of things that my school doesn’t teach us. I think it’s important that more young black people come to visit and learn about their history.

One visitor put it simply:

“I am changed.”

Isn’t that exactly the effect uncovering history should have? When we want to find out about what it means to be an American, if we want to really talk about racism and poverty and injustice, this is where we have to take the discussion: back to the plantation house and the people who lived and were forced to live in it.

If the footprint of the old Hogan-Rogers house, with the basement exposed, is allowed to remain as a testimony to this chapter of Chapel Hill’s past, many more people will be changed by what they discover. The foundations can continue to tell the story of the house and its people for centuries to come. And we will be honoring Harriet who would want her story and her people’s stories, to be told.

According to local African-American history, it has always taken a village to raise a roof. And in the spirit of this tradition, parishioners at St. Paul’s AME church pooled resources to purchase the land. Just days after the house was razed, someone had placed a bench and a brick pathway just a few hundred yards from the homesite. The individual bricks reveal that a new chapter of the house is about to begin and that the stories of the women, men, and children who lived in its dark depths finally will be brought to light.