UNC’s liberalism would soon be put to the test. (www.paulimurrayproject.org)

In 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt visited Chapel Hill, North Carolina, as he had done on a number of prior occasions, to accept an honorary degree. When he accepted the award, he called the University of North Carolina “a great institution of learning that was thinking and acting in terms of today and tomorrow and not merely in the tradition of yesterday,” and declared:

I am happy and proud to become an alumnus of the University of North Carolina, typifying as it does American liberal thought through American action.

But what FDR did not say was that this “liberal” university, like all Southern universities, did not admit African-American students even if they met the other admission criteria. When African-Americans wanted to attend college in the South, their only option was to matriculate at a “Negro” college, today referred to as HBCs (Historically Black Colleges).

If a Black student sought to study medicine or law or another subject not offered at “Negro” colleges in North Carolina, the state met its legal obligation to provide all children with access to education by giving them the option to attend a university “up North,” in this way upholding the strict separation of Black and White under Jim Crow.

Not all North Carolinians accepted this arrangement. In fact, just a few months before FDR received his honorary degree in Chapel Hill, a young, Black woman from Durham challenged UNC’s racist order by applying for admission to the law school. Emboldened by a keen intellect and a proud family tradition in education, Pauli Murray pursued the matter by going straight to the top.

A remarkable new book entitled, The Firebrand and First Lady describes the relationship between Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt that began when Pauli wrote to her husband, the President, furious that he had not taken a firm stand against lynching and white supremacy. She wrote:

It is the task of enlightened individuals to bring the torch of education to those who are not enlightened. There is a crying need for education among my own people. No on realizes this more than I do. But the un-Christian, un-American conditions in the South make it impossible for me and other young Negroes to live there and continue our faith in the ideals of democracy and Christianity.(as cited in Bell Scott, 27)

Then, alluding to the looming crisis beginning to consume FDR’s political agenda, she added: “We are as much political refugees from the South as any of the Jews in Germany.”

Finally, she challenged him by quoting directly from his acceptance speak at UNC:

You called on Americans to support a liberal philosophy based on democracy. What does this mean for Negro Americans? … Does it mean, that as an alumnus of the University of North Carolina, you are ready to use your prestige and influence to see to it that this step is taken toward greater opportunity for mutual understanding of race relations in the South? (as cited in Bell Scott, 28)

Murray included a letter for Mrs. Roosevelt, making reference to a brief encounter between the two women a few years earlier, imploring her to “try to understand the spirit and deep perplexity in which it is written.”

With this letter, the friendship between Murray and Eleanor Roosevelt began; it intensified through correspondence and meetings over many years until Roosevelt’s death in 1962.

Murray was never accepted at UNC, despite personal petitions to President Frank Porter Graham, a personal friend of the Roosevelt’s, who seemed to sympathize with her pleas but felt it would not be politically expedient to honor them.

Gwendolyn Harrison Smith- first black woman to be admitted to a graduate program in 1951. The university first admitted her as it did other women on a case-by-case basis, not realizing she was African-American, then attempted to revoke her admission when their error was discovered. Harrison Smith, who had earned a BA at Spelman College and the and a master’s degree at the University of California, fought UNC’s policy and won, but left before finishing her degree. (Source: blackmattersus.com)

Murray went “up North,” graduating at the top of her class at Howard Law School. There, she met a man who became instrumental in desegregating UNC and later became the first Black Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall. Murray wanted to continue her education and applied for a fellowship at Harvard Law School. Interestingly, Murray was rejected by Harvard despite impeccable credentials, not because she was Black but because she was a woman. Murray spent her life fighting on both fronts.

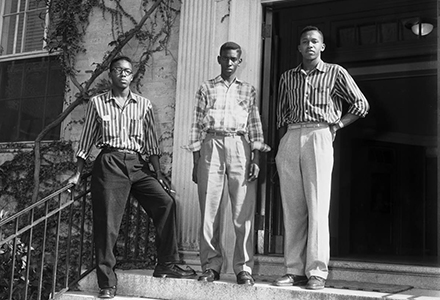

Ralph Frasier, John Brandon and LeRoy Frasier, Jr., on the UNC campus in 1955 (Source: unc.edu)

It wasn’t until the landmark 1954 Supreme Court Brown v. Board of Education decision that legal challenges to racist admission policies met with success. After a series of law suits, UNC was forced to accept black undergraduates for the first time in 1955. Three graduates of Hillside High in Durham– John Brandon, Ralph Frasier and LeRoy Frasier, Jr.– started together amidst vocal opposition by the Board of Trustees, as well as many administrators, faculty members and students. This antagonism was one of the main reasons all three of UNC’s first black undergrads left Carolina and graduated from other universities.

Pauli’s legacy, as well as Gwendolyn’s, Ralph’s, John’s and LeRoy’s and those of so many other pioneers, lies in questioning what liberalism has meant for the cause of racial and social justice. Though we often assume, wrongly, that the two are connected, they aren’t, neither in theory nor in practice.

In theory, liberalism offers freedom from restrictions and limitations, legal or otherwise. Liberalism is much closer to what we know as libertarianism, rather than social progressivism. Progressives rely on government and other mechanisms of power to level the playing field, to equalize opportunity, even if this means coercing resisters. Historically, liberals often have defended the idea of equal opportunity and fair competition, including equal access to education.

And yet it seems that in our university town, many liberals seem more concerned with securing resources for their children than creating a level playing field. I wonder if this is the case in other college towns that pride themselves on their good public schools. Among white educated families in Chapel Hill, the unlevel playing field is tolerated or ignored in the face of blatant inequality.

For centuries, liberal elites tolerated racial and gender-based barriers that denied education to a majority of US citizens. Despite demands made by social movements and activists, those with power to change things have accepted exorbitant higher education costs, even though these clearly limit access to the country’s best universities to all but a very small upper-middle class and wealthy minority.

Here in the state of North Carolina, tuition for state universities are often too costly and application requirements too complicated for many potential first-gen applicants. Even the community college system charges more than many kids can afford. And those who get in, often don’t make it through. Is enough being done?

If Chapel Hill is any indication, liberals do no better at creating conditions for educational success of African-Americans than elites in other towns do; in fact, the opportunity gap in town hasn’t changed much since segregation ended. And local elites aren’t really fooling anyone.

Source: Raleigh News and Observer (October 30, 2015)

Pauli knew it; and she called UNC on it. Today her voice would most likely join the chorus of those teachers and parents who still regularly challenge town elites. Like Pauli and Gwendolyn and Ralph and John and LeRoy, local activists today speak their truths, then work with anyone who is willing to meet with them. So many local activists have simply not given up despite disappointment after disappointment. I’ve met many of them and the story is pretty much always the same. As one local minister said to me yesterday, “Politics are heavy in this town.”

And somehow enough people have been audacious enough to keep pushing for change.

For more on Pauli Murray, click here.