…you saw those people being in your community, and then as you continued to get a little older, you would see these people as entrepreneurs —how fascinating, you know, to just be able to see the same common people that you would see all of the time as business people too.

Pat Jackson, 2011

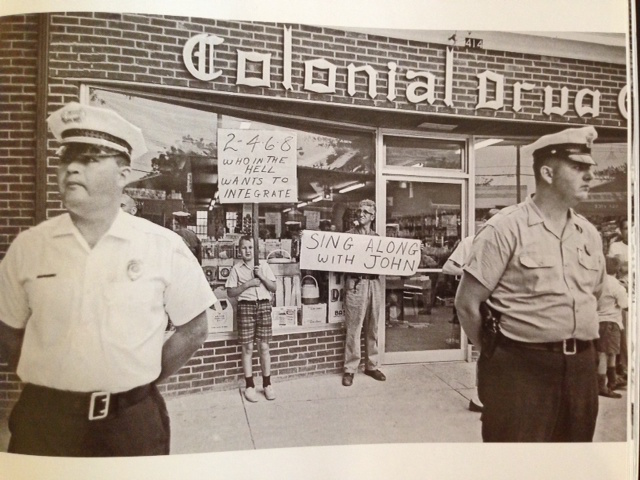

If you’re familiar with Jim Wallace’s photos of the civil rights movement in Chapel Hill (many of which have been featured on this blog), you can see what it took to get many white merchants in downtown Chapel Hill to desegregate their stores. Pictures show students and residents picketing restaurants like the Pines, Brady’s, and the Dairy Bar on Franklin; sitting at lunch counters where they were taunted and refused service; carrying signs, marching and pointing their fingers at businesses like Colonial Drug and Joe’s; enduring verbal and physical attacks; and being arrested by the local cops.

Other white-owned businesses served black customers but generally did not make them feel welcome. Northsiders tell story after story about having to enter businesses from back entrances and waiting for service after all white customers were served first. Less often remembered are the many businesses in town that not only served black people; they welcomed them with open arms. And today, there are few traces of them in downtown Chapel Hill.

Northside resident Chelsea Alston remembers how things used to be: “I’ve heard stories from people that were around when there were Black owned businesses and most people that owned those businesses were family members or they knew the kid’s parents. It was really easy for them to come in and just hang around and don’t have to worry about safety or anything. Or parents being worried about where they were at because they knew the person that owned the place so they knew they would be fine, their children would be fine. So if there were more Black owned businesses there would be more places for African Americans to go and hang out.”

Black owned businesses were mostly what we call “micro-enterprises” today; they emerged from very few resources since Chapel Hill banks did not lend to blacks. They emerged out of the need for goods and services including ambulance and basic medical services, since black residents were underserved and in many cases not served at all. And businesses arose out of the need for income since many of the jobs available to black residents were very poorly paid. Most families needed multiple sources of income to make ends meet.

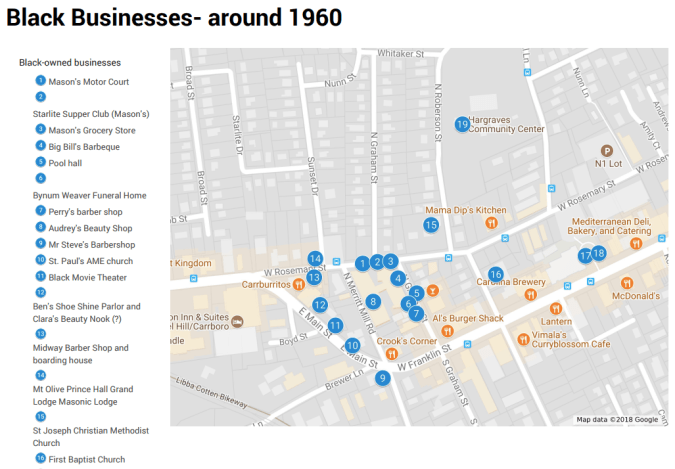

The area bordering the Northside neighborhood, especially a few blocks on West Rosemary and North Graham Streets, was known as Chapel Hill’s black business district. Northsiders could shop for groceries there, get a haircut, buy some barbeque, listen to music. Black travelers who were refused a room at Watt’s Motel and everywhere else in Chapel Hill could check in to Mason’s or one of the boarding houses in Northside and get a good night’s sleep. While they couldn’t get a table at the Pines, Northsiders could get front-row seats at Charlie Mason’s Starlite Supper Club and listen to world-renowned musicians including Ike and Tina Turner, James Brown, and Ella Fitzgerald. If you were an expert bricklayer, wanted to do good for your community, there happened to be a Prince Hall Grand Lodge Masonic Temple that recognized black stone masons, right on the Carrboro-Chapel Hill border on West Rosemary. You called Bynum Weaver’s if you needed an ambulance or had to arrange a funeral; or you could go to Weaver’s market and get some candy while your mama had her hair done by Miss Susie Weaver in her beauty shop. And nobody minded—in fact, it seems it was expected– that you lingered a bit and caught up on local gossip or asked about family members.

Today, only 3.6 percent of local businesses in Chapel Hill are Black owned, and towering over the center of what once was known as the Midway District is Greenbridge, a six-story building of luxury condominiums, a fitness studio and a start-up company that cater to a more affluent set. In the words of Willis Farrington, who grew up a few blocks away: “This thing has taken up probably about six or seven either homes or … Black owned businesses where this mass of building now stands.” Bynum Weaver’s is still there; now it’s called Knotts Funeral Home, but it looks pretty much like it did. It’s still black-run and Black owned, and there’s still enough local demand for a family-run place that knows its customers.

And of course there’s Mama Dip’s, run by Mildred Council since 1976, a time when many of the black businesses she grew up with were going out of business. Many locals today point to Mama Dip as an example of a thriving Black owned business, but Mama Dip and many Northsiders remember a time when dozens of Black owned businesses lined the streets and local residents frequented a place called Bill’s Barbeque. As Mr. Farrington tells it: “Before they even thought of this Greenbridge, used to be Bill’s Barbeque. And Bill’s Barbeque was where Mama Dip pretty much, from what we – those that know her and know him—got her start, from their little restaurant used to sit right here. And had the best chicken sandwiches and chuck wagon sandwiches and hot dogs in town.”

In addition to the official storefront businesses, Chapel Hill’s black neighborhoods were home to a vibrant and essential informal economy. The neighbors knew where to go if you needed a ride, hauling, medical services, a boarding house, a good meal, laundry services, child care, auto work, household repairs, sewing work, masonry, medical attention, a floral arrangement or some fresh produce. Joe Farrington used to grow vegetables on his backyard plot; when the corn and the sweet potatoes were ripe, he recalls, neighbors were invited to come and get some.

Like pretty much anywhere else in the world, an informal economy emerged in Chapel Hill because the entrance to the formal economy was blocked by segregation and the many manifestations of racism from depressed wages to lack of financial services to the threat of violence. The cost of doing business with white people – even if not officially prohibited — was often much too high. Clementine Self grew up on Graham Street and participated in many of the civil rights demonstrations in the early sixties when she was in high school.

She and her mother, Lucy Farrington, describe the scene in downtown Chapel Hill to interviewer Hudson Vaughan:

Lucy Farrington: And I remember when the man at the drugstore wouldn’t let me have no sandwich. I got into a whole lot.

Clementine Self: That was Colonial Drug.

Hudson Vaughan: They took the booths out too, didn’t they?

CS: Yeah, they took the booths out so that we couldn’t sit down. So they decided no one would sit. Everybody would have to stand or leave. And Brady’s, which is, what is it? 501 now, I think it’s called. It’s right in front of Trader Joe’s.

HV: Yeah, yeah. Okay. Right in front of Trader Joe’s. CS: But on the street.

HV: Like towards Route 15/501?

CS: Yeah, it faces 15/501 when you come down, like if you’re coming down 15/501, there’s a restaurant sitting over there to the right?

HV: Okay.

CS: That was one of them. And then there was another one further down Franklin St. I just don’t remember what the name of that restaurant was. It was like, sort of remind you of a drive-in, in a way. With a thing over it, like a car shed over it. And you would drive up and get your milkshakes. You know how the kids, they didn’t do it here, but some cities they skate to the car and bring you your, it was that kind of atmosphere.

HV: Oh yeah. Gotcha.

CS: That was one of them. We couldn’t go in there either. But the thing about Chapel Hill, though, many of our community people, we had a lot of Black business people in Chapel Hill, so we really didn’t have to go to those places if we didn’t want to. … So, there were businesses we could go to without having to venture out. [Emphasis mine]

Delores Bailey remembers this too. As director of the first community development organization in town, EmPOWERment, in the Midway district, she has dedicated herself to bringing back small businesses that cater to neighborhood residents. She knows better than anybody that neighborhood businesses, along with churches, schools, and affordable housing are the pillars that will keep the community alive.

Many Northsiders will tell stories about the humiliation of entering white businesses from back entrances or being denied entrance at all; and then they’ll talk about the joy they felt when they got away with sneaking to Weaver’s store during school and getting a snack for themselves. The comfort of being recognized and welcomed in the “black world” contrasted sharply with the sense of fear and danger black kids felt when they crossed into the “white world.”

Most people talk of those days in positive terms; black–owned stores were places, like the schools and churches, where community pride and cohesion developed; merchants provided opportunities for young people to earn some change and for older folks to share local news.

When you take a look at what downtown Chapel Hill looked like in the 1960s, you’ll ask yourself, “Where did all that opportunity go?”