Chapel Hill High then and now…

But I just told him, your generation’s dying, dad. We’ll take over from you and we’ll do it our way now. Bettie F.

On one of the many unseasonably warm days this December, I had the chance to talk with a friend in the Carol Woods Retirement Community in Chapel Hill. Bettie is white, a soft-spoken eighty-something with a warm, welcoming demeanor. As we sat sipping tea in her living room, surrounded by walls and shelves full of mementos from the rich intellectual life of a traveler and educator, she spoke freely and modestly about her life journey. She is the sort of person who appears worldly and cosmopolitan, so that it is a bit surprising when she starts by revealing her deep roots in the rural South. Like many Southerners I’ve met, Bettie speaks honestly and directly about race:

My dad was from South Carolina, and he was very learned. But he was chemically a racist. But he was a gentleman. And if the maid was black and she picked up your sugar cube and put it in your cup like that, he didn’t blink. He just was perfectly happy with that because he was used to being around black people. And because you are civilized you speak well and you do not feel– . Anyway, and mom was a Christian. “Everyone is God’s child,” and all that jazz. And she just loved little pickaninnies. [laughs] Anyway, but she is genuine, and she tried to integrate her church.

Something about the way she tells the story, consciously including unflattering details without sentimentality makes it easy to ask for more. And Bettie graciously continued:

Dad had a rage, I think, about what happened to South Carolina. He was born in 1883; he’s much older than my mom. And his feeling was– he was born twenty years after his grandfather was killed at Chicamaugua, and that was the one who owned the farm and the plantation and so forth. And his other grandfather was killed, his father’s grandfather, and they lost the slaves, they lost the land, and the house was destroyed by Sherman’s raiders. Not Sherman, but the kind of riff-raff that went along with losing and all that. And he always talked about Reconstruction in South Carolina. But I came in absolutely with my mother’s ideas that everybody was deserving of an education; everybody should have good health; everybody should have respect and all the rest of it.

Bettie studied history, then traveled around the world to teach in private schools. She met her husband while teaching in Beirut, and they returned to the US when he was offered a university position. They had two children, moved around and ended up in Chapel Hill in 1964, just after the local civil rights movement had succeeded in pressuring local businesses to desegregate. School desegregation was underway but did not officially happen until 1967.

When I asked her what she thought of the reluctance of UNC and the Chapel Hill school board to desegregate as soon as it was ordered by the Supreme Court in 1954, she expressed disappointment with the leaders now usually credited with their progressive liberalism:

… it’s hard to accept that people like Frank Porter Graham [President of UNC from 1930-1949 ] also didn’t want to push it. They wanted it, but, I don’t know. My mother used to kick me under the table when I was mouthing off about things, because I couldn’t see any reason why you shouldn’t get together. [laughs] Couldn’t quite understand the deepness of the divide.

Bettie taught first at a private Quaker school, the first interracial school in the Chapel Hill area, before taking a job at Chapel Hill High School in the early 1970s. In the first years after desegregation, there were some tensions, culminating in a stand-off between some student protestors who opposed the way in which the white leadership often denigrated or overlooked black students, faculty, and traditions from the old Lincoln High school. What did Bettie notice when she arrived? How did she see the situation?

AW: Did you feel like the administration of the history department was trying to get people to —Black and White—to get along with each other? You know, was there any dialogue about the race—just addressing the elephant in the room sometimes about race issues?

BF: Oh no. Now granted I was hired right at the last minute after–. But no, I’m just friendly, so I got along.

AW: But there was trust among the teachers then? There wasn’t any—

BF: I don’t know what to say about that. I didn’t think the problem was the teachers, although I’m sure there were thoughts on the black teachers’ side on how privileged the white teachers were. I just didn’t hear it.

Bettie explains many of the issues in the school in black and white terms. A few former CHHS students told me that discussions of race had taken place in some classrooms. One teacher whose name came up a few times was the chairperson of the history department who taught the first classes in African American history. Mrs. Joyce Clayton would address racism in class and encourage students to challenge people to think about how to get along with each other.

Bettie is almost apologetic when she says she was primarily concerned that students learn the subject material and that students “should know things.” Her classroom was for learning about history and sociology, but that didn’t mean that learning didn’t get personal. In fact, Bettie took some bold steps to address race in her sociology classes:

I had a soc[iology] class and I was bringing a husband, who was black, and his wife, who was white, to talk about an interracial marriage. We were studying marriage at the time. And Pat was a very handsome, intellectual, competent leader in the community and one of the students got on her chair and yelled at him and yelled at him. I said, “You’ve got to leave the room.” So I finally got her out of the room and down the hall, yelling. I didn’t know what was wrong. And it turned out, she was a leader in the making of the Black community and here was a Black guy who wastes himself on a White woman. [laughs] I just had no idea. But he understood it very well.

Despite the tension apparent in the situation, in her humble and straightforward rendering I imagine students felt empowered to speak their minds on the issues of the day when they were in her classroom. Few teachers today would be as bold and passionate as to arrange for very personal discussions about race the way that she did. In fact, by encouraging students to discuss their own views and experiences in the classroom, Bettie clearly found ways to make sociology meaningful and relevant. I’m certain most students did not forget this lesson, though I wonder how they processed the discussion and what the different take-aways were.

Bettie’s own children had African-American friends and her daughter had a number of Black boyfriends.

…the one thing I thought that was good that was worked out was the Chapel Hill Preschool that was started at the Community Church in the sixties … and they matched the kids —one black to one white. And those kids knew each other all the way through school. And it didn’t work perfectly but they were used to each other.

She is quick to add this is not to suggest she or her children somehow are free of racial bias. When she recounts those experiences, she still thinks she could have done more, learned more, to build a better understanding of race and make more connections to members of the Black community.

She enthusiastically reported on a forum she’d been to at her retirement community. Two women, one black and one white, talked about the book they had written together about attending Hillside High School in Durham at the time it was being desegregated. (For a link to the book by Cindy Geary and LaHoma Romicki, Going to School in Black and White, click here.) Unlike Chapel Hill High, white students were bussed to all-black schools, as well as the other way around. At Hillside in the 1970s, white students and faculty were in the minority.

The people in that book, both people white and black, had lots to learn about the other. I don’t know. I did not do that. I was just trying to teach history. I thought that was over with. I didn’t realize – maybe– since it was not by any means over with.

Perhaps the fact that desegregation was a one-way street, where Black students and teachers were always made to feel they had to catch up, that they were “lesser,” explains why integration has failed in Chapel Hill. Students are still separate, opportunities are anything but equal. The past defines the present.

Bettie challenges every one, no matter how committed to equality we say we are, no matter how smart we think we are, no matter how educated, no matter how far we think attitudes toward race have evolved, to begin by changing our attitude:

I’ve been awakened to stop being so smug. These issues are deep within us and going on still.

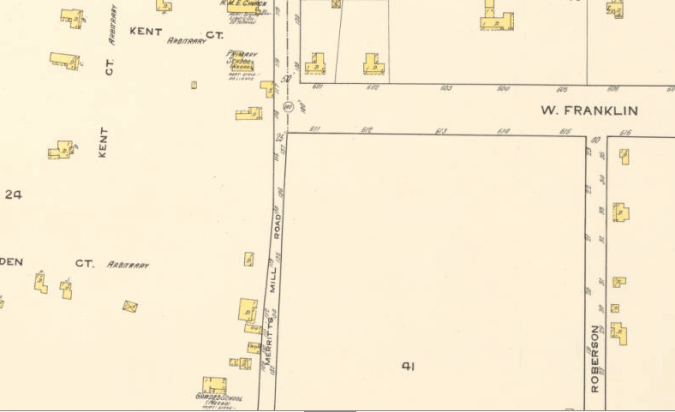

Carrboro, right next to the railroad tracks where Franklin turns to Main. The map shows this neighborhood, dated “1915.” Featuring prominently on the map are the various mills owned by Julian Carr, after which the town had been named just a few years prior to the year the map was drawn. Scattered among the mill buildings were a few houses, stores, churches, and a few schools, including the “Negro Primary School” and the “Negro Graded School.”

Carrboro, right next to the railroad tracks where Franklin turns to Main. The map shows this neighborhood, dated “1915.” Featuring prominently on the map are the various mills owned by Julian Carr, after which the town had been named just a few years prior to the year the map was drawn. Scattered among the mill buildings were a few houses, stores, churches, and a few schools, including the “Negro Primary School” and the “Negro Graded School.”

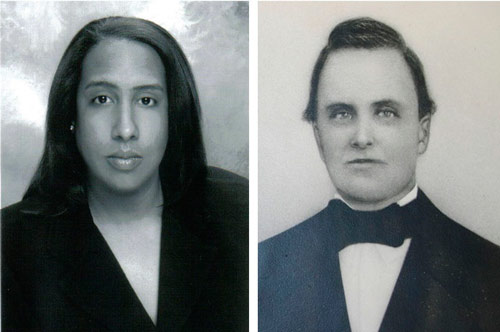

from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head.

from Appomattox, I horse-whipped a negro wench until her skirts hung in shreds, because upon the streets of this quiet village she had publicly insulted and maligned a Southern lady, and then rushed for protection to these University buildings where was stationed a garrison of 100 Federal soldiers. I performed the pleasing duty in the immediate presence of the entire garrison, and for thirty nights afterwards slept with a double-barrel shot gun under my head. I think that anyone who hangs a map like this on a wall must think about what the map tells us about the time it was created. This map is full of meaning, a visual reminder of an unjust social and political order. Such a sign of the past should raise questions and yet, as decor, it does the opposite. It normalizes and romanticizes by encouraging a comforting nostalgia. And while donuts should always be considered comfort food, the chapter of the town’s history on the wall should always make people stop and think about what that history meant for those who lived through it, as uncomfortable as that will be for some. The past is also our present.

I think that anyone who hangs a map like this on a wall must think about what the map tells us about the time it was created. This map is full of meaning, a visual reminder of an unjust social and political order. Such a sign of the past should raise questions and yet, as decor, it does the opposite. It normalizes and romanticizes by encouraging a comforting nostalgia. And while donuts should always be considered comfort food, the chapter of the town’s history on the wall should always make people stop and think about what that history meant for those who lived through it, as uncomfortable as that will be for some. The past is also our present.

volunteers; and they are bonding with each other, the way kids do– just by being around each other day in and day out and sensing that they are being treated equally and with respect by the adults in the room.

volunteers; and they are bonding with each other, the way kids do– just by being around each other day in and day out and sensing that they are being treated equally and with respect by the adults in the room.![Hargraves_4[1] Hargraves_4[1]](https://i0.wp.com/chapelhillstories.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/hargraves_41.jpg?w=335&h=251&ssl=1)

![Hargraves_3[1] Hargraves_3[1]](https://i0.wp.com/chapelhillstories.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/hargraves_31.jpg?w=333&h=251&ssl=1)

And yet, he also had a reputation as a generous employer. The town, known as Westend, was renamed “Carrboro” after he paid to have electricity brought to the area in 1909. He opened a textile mill, creating jobs for hundreds of workers and demand for new small businesses. And the events he hosted for his employees and their families earned him a reputation as a magnanimous boss.

And yet, he also had a reputation as a generous employer. The town, known as Westend, was renamed “Carrboro” after he paid to have electricity brought to the area in 1909. He opened a textile mill, creating jobs for hundreds of workers and demand for new small businesses. And the events he hosted for his employees and their families earned him a reputation as a magnanimous boss.

And the town has garnered accolades like “most livable small cities in America.” Even the New York Times can tell you how best to spend “36 hours in Chapel Hill,” and, in October the travel section of the London daily, The Guardian, featured Chapel Hill as one of the top ten best small towns and cities in the US. The question of course is, “Best for whom?”

And the town has garnered accolades like “most livable small cities in America.” Even the New York Times can tell you how best to spend “36 hours in Chapel Hill,” and, in October the travel section of the London daily, The Guardian, featured Chapel Hill as one of the top ten best small towns and cities in the US. The question of course is, “Best for whom?”